Franklin Stein

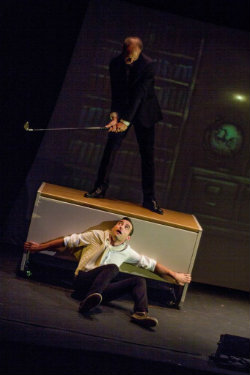

Anton Koval (Above) and Brett Epstein (Below) in FRANKLIN STEIN. Photo by Daniel Robinson.

BOTTOM LINE: A show about a dead man doing what he can to stay alive.

Franklin Stein (Anton Koval) has no heart beat. That’s what Dr. Sam’s (Larry Greenbush) diagnosis is after examining his stiff neck. From there the play follows Franklin as he unwillingly comes to terms with his situation: he’s dead, yet for some mysterious reason he’s still walking, talking, and basically functioning. Really, at its core, Franklin Stein is a metaphor for the way in which we occasionally go through life, feeling as if we were alive, but never stopping to ask ourselves if we’re really living or if we are just shells of humans going about our daily routines. The point is well stated and clear; however the play itself is too on the nose and consequently takes itself a little too seriously. Billed as a dark comedy/horror, the show has a few fun elements and laughs but ultimately it is a morality tale with heightened drama in lieu of potential farce.

As Franklin slowly disintegrates throughout the beginning of the play his struggles to seem normal and deny obvious indications that he is dead (i.e. his rotting feet and broken neck) are comical. We are introduced to his loving, airheaded wife Hope (Jennie West) and his self-assured, golf-loving coworker Buddy (Brett Epstein). It is clear that the people that populate Franklin’s world are alive, but are they really living? A final character is added to the mix, a loud-mouthed homeless man played by Xavier Reminick. After an attempt to cure himself by traveling to a sleazy “Zombie Master” (Emmanuel Elpenord) Franklin decides to take the doctor up on the only solution that seems he has left: he’ll need to find a human heart...one that’s still beating.

Franklin Stein is built around its message, in that every scene serves to reiterate the point of the play. This, at times, leads to redundancy and the repetition wears thin, leaving moments where actors talk in circles, usually punctuated by unnecessary yelling. For instance, when Franklin constantly questions Dr. Sam as to his condition, how he could be alive and dead at the same time, Dr. Sam only responds with vague answers, leaving Franklin with no choice but to ask the same questions, louder. The performers make this work to their advantage on occasion, as with Epstein’s hilarious, quirky/off-kilter deliveries or Koval’s use of physicality to entertain, often times throwing himself about the stage like a rag doll. The commitment is admirable and Koval believably plays a dead man walking. Greenbush is maniacal in a subtle way, portrayed by a soothing voice and calm stance. It contrasts well with Koval’s bold physicality.

The piece holds a great commentary on life and asks the right question to get the audience thinking. With a simple set design and direction the play takes you to a world where a man like Franklin could believably die and keep on living. I think the piece would have been better served committing fully to comedy, horror, or drama instead of the mildly confusing blend of all three. That said, the actors give the show plenty of energy and a few surprises keep the audience engaged. Franklin Stein is an everyman in a lot of ways and therefore this play is about every one of us.

(Franklin Stein plays at The Connelly Theatre, 220 East 4th Street, through September 14, 2013. Performances are Tuesdays through Saturdays at 8PM. Tickets are $25 and are available at franklinstein.brownpapertickets.com.)